Last year marked a turning point for the Army.

After several years of drawing down, the service got approval to give the active component a 26,000-person infusion, bringing the total force back to just over 1 million.

That was the plan, at least.

With a limited recruiting environment, hundreds of Army Reserve soldiers jumping to the active component, and a healthy economy, the Army has struggled to keep its 1.018 million total end strength from fiscal 2017 afloat.

The active Army, Army National Guard and Army Reserve together total just under 1 million soldiers, the Army’s personnel boss told Army Times on April 27.

The service has just five months left to get that number up to the latest National Defense Authorization Act’s 1.0265 million.

“It’s a tough market out there, but having the Army grow is a good challenge to have,” Lt. Gen. Thomas Seamands, the Army G-1, said.

Winter and spring are historically low months for end strength, officials say, as post-graduation recruiting tapers off. Things generally pick up in the fall and summer, after high school and college graduations.

The good news, Army Secretary Mark Esper told reporters on April 20, is that retention is at a historic high, up to 86 percent from the typical 81 percent.

“It tells me that soldiers like what they’re doing,” he said. “They like their service in the military.”

Which is good news for a service fighting to grow while faced with a high operational tempo, a shrinking pool of prospective new soldiers, and a mandate to both modernize its equipment while completely rethinking what it will take to win future wars.

“The Army is the most demanded service by the combatant commands,” Esper said. “In other words, over 50 percent of the requirements from the combatant commands involves Army soldiers.”

As such, the service is trapped in a deployment to dwell time ratio of about 1 to 1.2 — even though the goal for years has been to level it off at 1-to-2.

“The challenge right now with this mismatch between supply and demand, you see our soldiers on this hamster wheel of constant deployment churn,” Esper said.

A larger force would distribute the workload, if the Army can make it happen.

“My view is we need to be above 500,000 [in the active Army], with associated growth in the Guard and Reserve,” Esper said.

Recruiting challenges

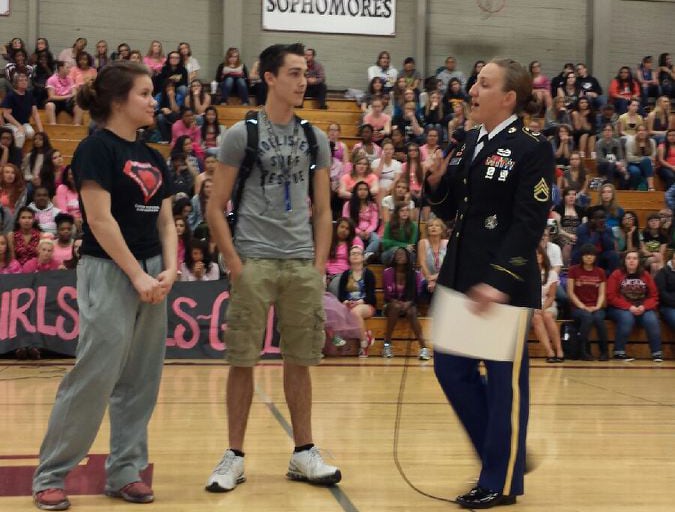

In early April, Sergeant Major of the Army Dan Dailey sent an email to senior enlisted leaders, warning them that the Army is short 400 recruiters and that they’d soon be receiving instructions to send their qualified noncommissioned officers on three-month, temporary recruiting duty beginning in May.

The email itself was premature, Seamands said, as top Army leaders had only thrown around the idea of tapping soldiers who’d already completed a tour as a recruiter ― and thus have the necessary training ― to help with the busy months.

“That was an option that was discussed, but it was never executed,” Seamands said.

The message did make public, however, that the Army is short on recruiters. To be precise, 90 percent of the service’s recruiter jobs are filled, Army spokeswoman Lt. Col. Nina Hill told Army Times.

The biggest reason for this, Seamands said, is that the recruiting mission has grown ― originally 80,000 this year ― while the recruiter ranks have hobbled along to keep up.

“When we make a decision to grow the Army like we did last year and this year, it’s about nine to 12 months before you can effectively grow the recruiter strengths,” he said.

Sending former recruiters on emergency TDY is one way to address the issue. but also one of the more extreme options.

“You could rush to failure and put people there with no notice,” Seamands said. “You could rush to failure and put people there with no time to prepare.”

No decisions have been made yet, but he added that the Army has been “working for months” on a solution and is trying to take a “deliberate approach.”

“We’ll have those filled up by the end of the year,” he said.

In the meantime, the Army has lowered this year’s recruiting mission from 80,000 to 76,500. The move isn’t in response to slow numbers, though, leaders say.

Rather, it’s a re-balancing of end strength numbers. Last fall, during NDAA negotiations, the House and Senate jockeyed back and forth between increasing end strength by 5,000 or 10,000 soldiers.

The Army decided to shoot for the moon, setting the 80,000 goal in anticipation of growing by 10,000 by October 2018.

The NDAA met them in the middle, with a growth of 7,500, giving the service room to reduce its retention or recruiting goals to accommodate the smaller growth.

NCO surge

Meanwhile, retention has surged a full 5 percent so far this year. And rather than shut off the flow, in March the selective retention bonus program expanded, adding infantry, armor and medic MOSs, despite how crowded those career fields tend to be.

The Army had already met its retention goal for the year, senior Army counselor Sgt. Maj. Mark Thompson told Army Times in April, and decided to push forward with keeping even more soldiers in uniform.

The Army set a goal of 52,000 for fiscal 2018, Seamands said, or about 85 percent of those who would be up for re-enlistment this year. As of late April, he added, they were more than 1,000 soldiers over the goal.

Not only do the retention numbers take some pressure off of recruiting, but leaning on experienced soldiers to build end strength is part of a larger shift.

“I’m not sure we need to bring in fewer recruits,” Seamands said, but on top of growing the Army, the service is also eyeing extending the length of basic training.

This will require more drill sergeants, particularly in the one-station unit training programs that feed the most populated military occupational specialties.

“The first thing you have to do is increase the generating force,” Seamands said of the NCO corps. “So you have to make that investment, and a lot of them are infantry and armor.”

NCOs are at a premium, with re-enlistment bonuses ranging from $1,200 for some E-5s to stay on for one to two years, up through $72,000 for some E-6s and E-7s to commit to at least five more years.

And then there are the Security Force Assistance Brigades, which need hundreds of NCOs to man all six that the Army plans on standing up.

Looking ahead

Officials are optimistic that the Army will reach its total force goal by the end of the fiscal year, and are looking to add yet more soldiers in fiscal 2019.

“We’ve asked Congress to grow another 4,000,” Seamands said of recent hearings and meetings leading up to the next NDAA.

Retention bonuses are a sure-fire way to keep enlisted leaders in the Army, but other measures, like Esper’s push to eliminate a host of online training, could help increase morale.

“If you ask a soldier why they came in the Army, they came in the Army to learn, to grow, to travel,” Seamands said. “If we sit them in a class with a PowerPoint two days a week because the Army’s told them to, they’re less inclined to stay, because they’re not inspired by it.”

On the recruiting side, the Defense Department estimates that about 20 percent of Americans ages 16 to 21 will take steps to join the military, but that statistic has to square the roughly one-third of those Americans who meet minimum enlistment standards.

“One thing we’ve got to figure out how to do is increase propensity,” Seamands said of Americans who are medically and physically qualified to join.

RELATED

There are a variety of ways to make service more attractive to young people, leaders say. One is enlistment bonuses, which went way up during the 2017 build-up.

Another is flexible commitment terms. In 2017, the Army offered two-year enlistments, both to attract recruits who wouldn’t have otherwise signed on for a full four years and to get the numbers up, with the hope that many of them would love the Army and want to stay.

“We’re looking at things where, maybe you do three in the active and three in the Reserve,” Seamands said.

Currently, he said, the Army is looking at a shortfall of several thousand soldiers in the Reserve, which leaders attribute to the ongoing push to activate reservists.

“Just being completely candid, with the call to active duty, that advantages the active,” he said.“

The Army is also due for a marketing face lift, which could help the service tap into what Americans are looking for from military service, including technical training, education or even health care and other benefits.

And then there are attrition rates, either during initial entry training or later on.

Heightened fitness standards may help with that, Seamands said of the Occupational Physical Assessment Test, which measures basic fitness levels according to intensity of an MOS.

“You may have had an aspiration to be an infantryman, but if you didn’t have the physical capacity, what we would have done is we’d let you go and you wouldn’t make it through the training,” he said of pre-OPAT days.

Those trainees would either drop out or get hurt and have to be recycled or separated.

“Now we find a better alternative,” Seamands said, redirecting those with lower OPAT scores to different jobs. “If we can avoid people getting hurt, then you stay ready.”

For now, the focus is on getting to 483,500 in the active component by Sept. 30.

”I think it’s too early to tell whether we’re having a concern or not,” Dailey said April 20. “I have a really good indication that we’re going to continue to retain people at a historically high rate.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.