Benjamin O. Davis Sr. and Jr., were a father-son duo who, respectively, went on to become the Army’s first Black general and a four-star Air Force general who led the famed Tuskegee Airmen and helped integrate the U.S. military.

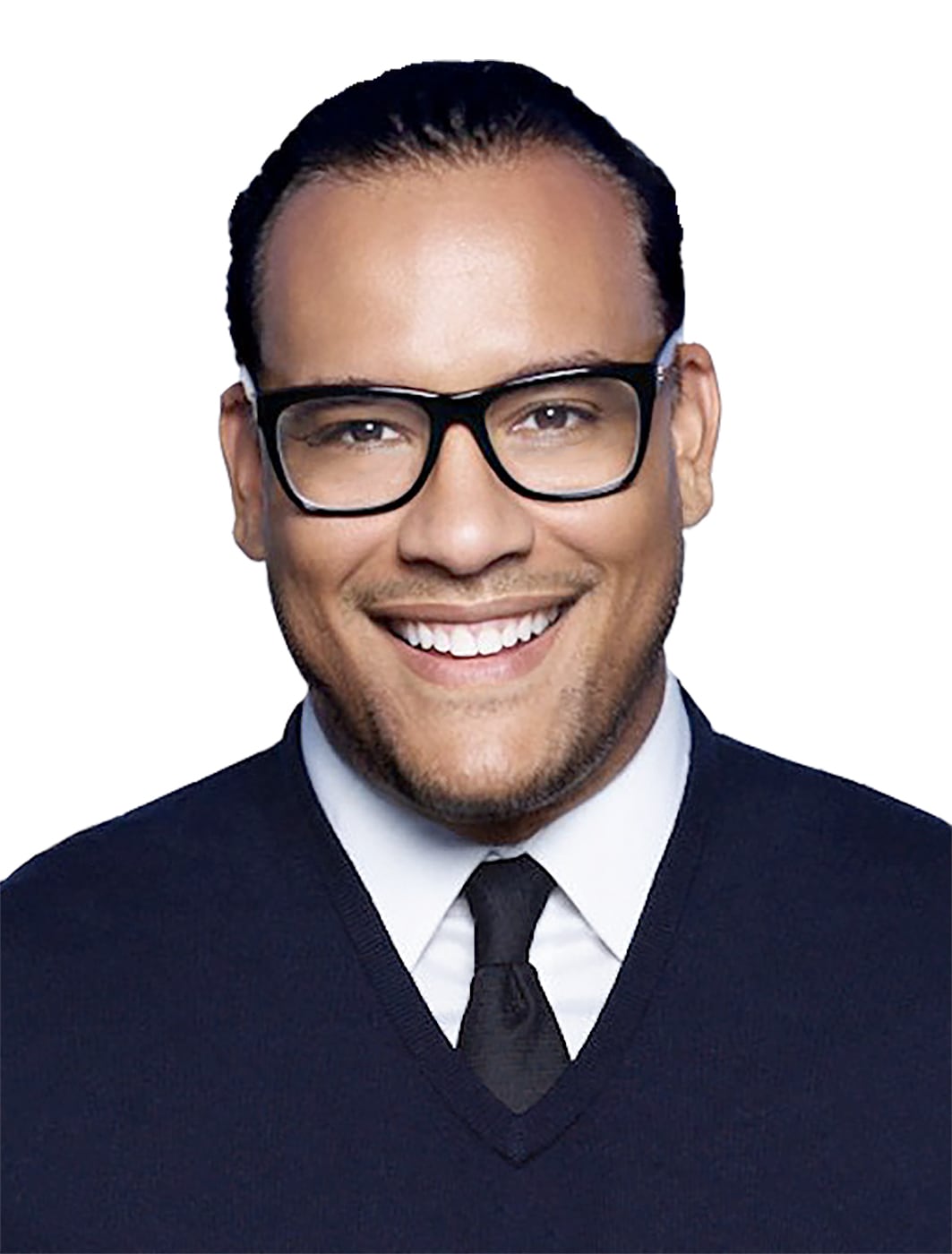

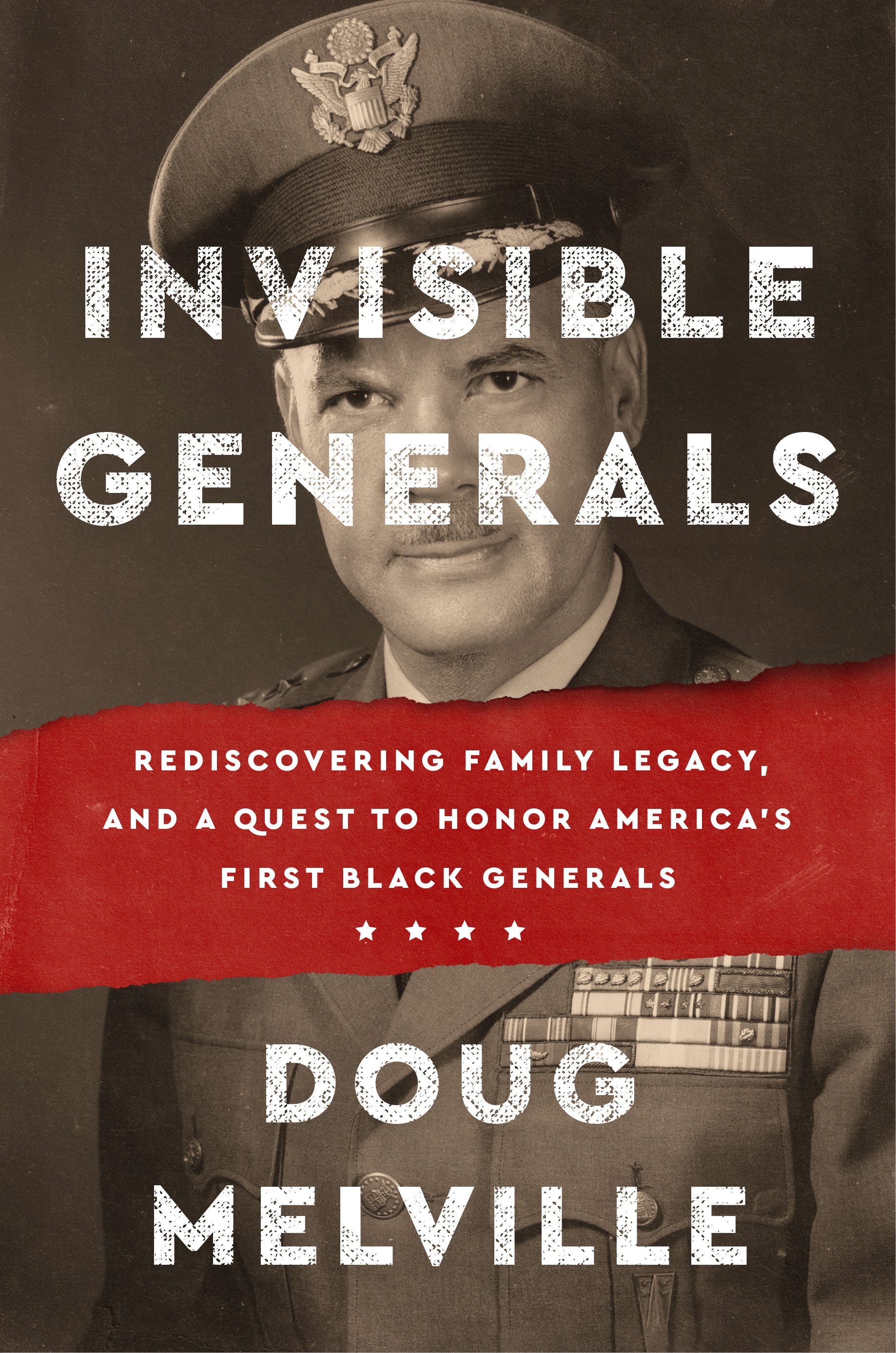

Doug Melville knew little of his family’s military legacy until he started asking his father, Davis Jr.’s nephew, questions that would lead to a decade of research. Melville combed through presidential libraries, museums and archives in his mission. The result of his work was “Invisible Generals: Rediscovering Family Legacy and a Quest to Honor America’s First Black Generals.”

Melville would learn of the challenges his family faced in a segregated military in both wartime and peace. In this book he shares a family, military and American story while also showing the steps he took, which others can follow, to uncover the invisible stories hiding in their family histories.

The following Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What inspired you to write this book?

A: The impetus for me to write this book was going to see the movie “Red Tails,” a 2012 film about the Tuskegee Airmen. I was invited to a screening of the film right before it came out. I was invited on behalf of the family of Gen. Benjamin Davis, who was the commander. And when the movie started, and the lights went down, and Terrence Howard walked on the screen and his name was not Col. Davis. It was instead Col. Bullard and when I looked around the room at the other Tuskegee Airmen in the theater, I realized that all the names from the movie, I would come to find out, had been changed from the original names. So, I went home and talked to my dad about it. To be honest with you, I was furious. He put everything in perspective. [Benjamin Davis Jr.] and his father raised my dad, he was their oldest nephew. My father said, “why don’t I tell you the story of the invisible generals, because that’s what they used to call them, because we had to live like we were invisible.”

Q: What did you know about Ben Sr. and Ben Jr.’s lives and military service before beginning the research?

A: I never knew anything about Ben Sr. I found out he was the first black general in American history when we got invited to the launch of his stamp. The U.S. Postal Service made a Black heritage stamp with his photo on it. As for Ben Jr. I really didn’t know what he did. I knew he was a pilot. I knew he was in the Air Force. He always wore a touch of red. And anytime we would go to Andrews Air Force Base, or the Pentagon people would salute him. But I never actually knew what he did. He didn’t have pictures on the wall of his home or medals or anything like that. In 1998 the family was invited to the White House because President Bill Clinton was going to pin his fourth star on him in retirement. That was when I really started asking a lot of questions. The family really didn’t talk about it.

Q: Why do you think the family didn’t talk about their achievements?

A: It was partly that they moved in a system where silence was security. If you really go back and look at their lives, the less people that knew what they were doing the better it was for them security wise and psychological safety. I think it’s hard for me to even understand a segregated Army. I mean the tools that they used on the Tuskegee Airmen’s planes couldn’t be used on white pilots’ planes. So, this was an extreme reality that they were living in. They told me later they didn’t want to burden me with the past. Ben Jr. never said anything good, bad or indifferent about the military. He just wanted my dad and me to look forward and do what we wanted to do.

Q: The book is part memoir, part history and part call to action. Why did you structure it this way?

A: I think the decision to structure it this way was really to put the family element in it and really bring the reader along on my journey. To say I was a normal person who got the opportunity to uncover an extraordinary part of history and an extraordinary part of my family that also helped me find my purpose. It was really about uncovering that story along with my own story. It helped me decide to change careers to become a chief diversity officer after the movie “Red Tails,” because I wanted to work with companies to ensure that those who were invisible or whose names could be changed had an opportunity to have someone at the table to defend them.

Q: What were some of the more surprising things you learned in your research?

A: I think the first, most shocking thing that I found out was that when Ben Jr. was at West Point no one ever allowed him to sit down and eat. So, when you’re a cadet there you ask permission to sit and for four years, three times a day, no one ever allowed him permission to sit. That was mind blowing. The second thing was that when Ben Jr. took command of the Tuskegee Airmen, he was in his late 20s. And he was responsible for 15,000 people in a 100% segregated military. The third thing I found out that was really shocking was when I visited the Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. I learned that it was at the war college where researchers wrote the report on the negro soldier in the 1920s which essentially limited their progress and opportunity because it published a variety of stereotypes with no doctors, no medical personnel on the committee, which ensured that blacks couldn’t operate machinery, couldn’t command white soldiers. Many of the things that became de facto policies were written in that report that was published by the war college. The irony of that is that Benjamin Davis Sr.’s collection of files, honors, paperwork and uniform are housed at the war college right next to the letter that they wrote to limit his career.

Q: The last section of the book is titled “Becoming a Visible General” and is a call to action. What do you hope readers will do with that?

A: At the end of the book, I share with people the process I went through to make an invisible history visible. I’ve had readers, dozens and dozens, go through the steps and find out someone in their family did something they didn’t know about. I’ve had people tell me one of their grandparents was in the Holocaust but never said anything until they started asking questions of them. For me that was a really special moment to know that people are uncovering their own stories. If I can have a takeaway from this book, it is that Black history is American history and that all these stories make up the tapestry that is America. If this story was invisible to even me in the family, can you imagine how many untold stories are out there from different people’s accomplishments, different people’s journeys that they went through that are all a part of American history but just aren’t written down? So that was the purpose of that part of the book, to say you can start your own journey, here are the steps I took. Here are the areas where I have found success. And why don’t you give it a shot as well?

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.