QUANTICO, VIRGINIA — Any Marine who has even a passing interest in the service’s history as it relates to special operations knows that when the Joint Special Operations Command was formed in the 1980s it brought together existing special operators from each of the services — except the Marines.

Future authors in their own memoir-publishing company Navy SEALs Team 6 along with the Army’s soon-to-be Chuck Norris movie franchise line Delta Force and the lesser-known Air Force 24th Special Tactics Squadron all formed up under the newly-tasked command.

It would take more than a quarter-century for Marines to form the Marine Raiders in the heat of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and join the party.

Back in the post-disco haze of the early 1980s the Marines were “special” enough, thank you very much.

And, by the way, why would the Corps offload some of its best hard-chargers for some Army general or Navy admiral to keep all to themselves? The pit bull stays with its trainer.

But jarheads deploying today on the Marine expeditionary unit rotations across the globe might not know why they have to punch through a list of tasks predeployment so they can tag their MEU with the designator of special operations capable, or MEU(SOC).

Well, leathernecks, Marine Corps Times has got you covered with the inside gouge, which was stumbled upon in the Marine Corps History Division Archives recently.

The answer was hidden deep in boxes inside the Alfred M. Gray Research Collection.

Who’s this Gray guy, you ask?

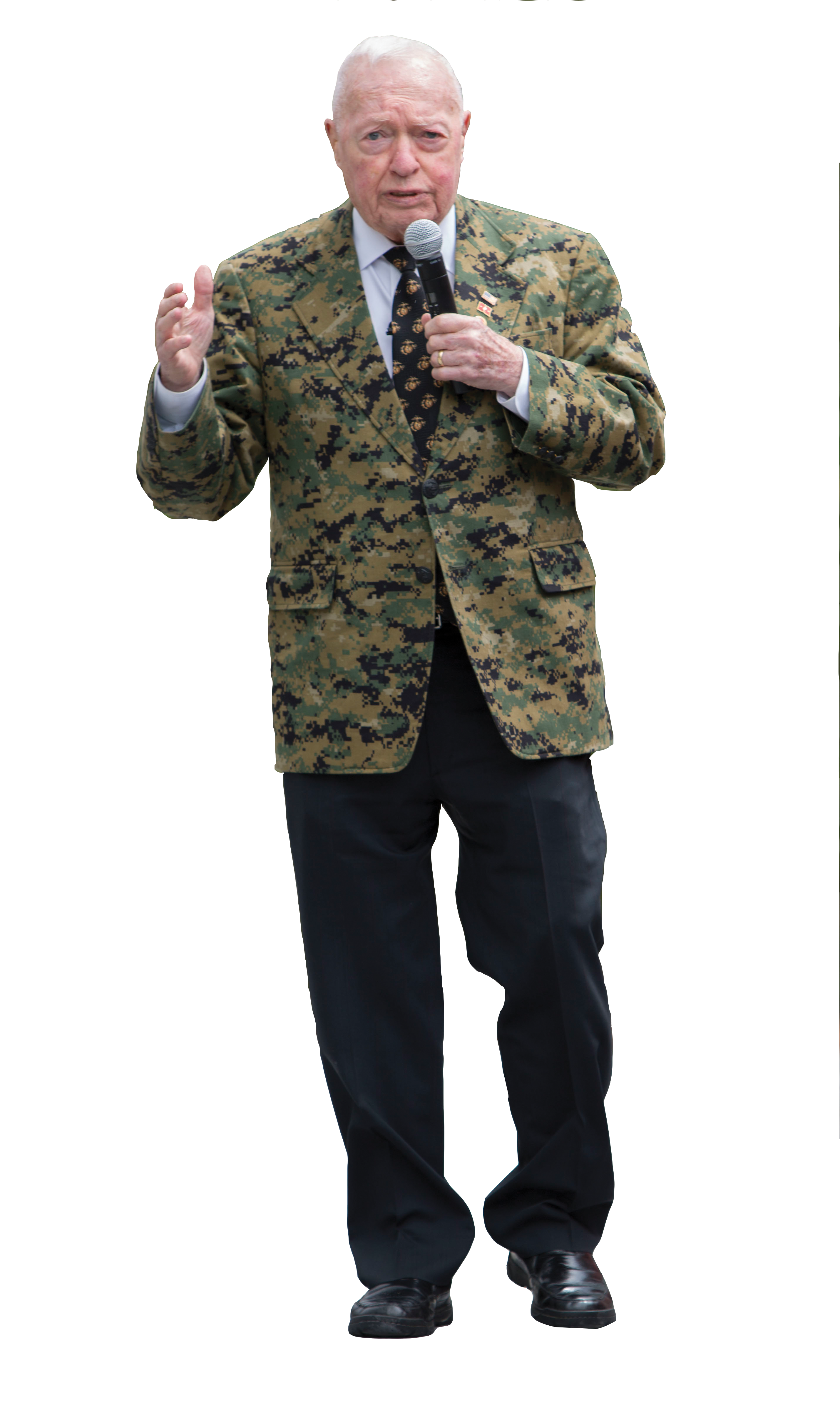

Well, he is what some very biased Marines consider perhaps the Corp’s greatest leader, a Marine’s Marine, a New Jersey native who enlisted, that’s right e-n-l-i-s-t-ed, in the Corps, served in both the Korean and Vietnam War, earned a Purple Heart and Silver Star Medal along the way to becoming the 29th commandant of the Marine Corps, serving from 1987 to 1991, retiring after 41 years in uniform.

Oh, and he’s the only commandant to have his official portrait taken in a field uniform. At least so far. Anyone got Gen. David Berger’s mobile? Didn’t think so.

So, show some respect.

Anyway, inside of those papers is a memo from one retired Maj. Gen. Mike Myatt to one Col. Gerry Turley. Myatt retired at the two-star level in 1995. But about a decade before, he served on the staff of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

While working for the chairman, he was monitoring training and took a little hop down to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, with then-commanding general of 2nd Marine Division, Maj. Gen. Al Gray.

For the duo’s in-flight entertainment, Gray bent Myatt’s ear, telling him of the Corp’s plans to create special operations capabilities for the Marine amphibious units, (a MEU precursor), deploying to the Mediterranean.

The move to put special operations under one roof, fund it, train it and sustain it, was driven largely by nightmare-level bureaucratic competition between the services for missions and money, but also by failures of the special operations community and planners who didn’t know how to use them, such as Operation Eagle Claw, a tragic attempt to rescue U.S. hostages being held in Iran that resulted in eight dead troops, including three Marines and five airmen.

Gray had served on the commission that analyzed what went wrong with the operation. Never again.

The rise of terrorist attacks in the 1970s spurred on efforts to tailor units to respond to that threat, which hadn’t been at the forefront of military planning.

But, back to our previously scheduled programming.

RELATED

Gray rattled off a litany of challenges that faced Marines in forming the MAUs to face this threat and more importantly, reasons why it had to be done.

The MAUs capabilities had atrophied over time, they couldn’t even do night operations effectively.

The Army had convinced the Pentagon to change the definition of special operations from environmental — arctic operations, jungle operations, etc. — to “…operations conducted by specially trained forces,” Myatt wrote.

This broadened what the Army could do by quite a bit.

And those sneaky soldiers had slipped in amphibious raids and noncombatant evacuation operations into the list, two important operations historically done by whom?

You guessed it, Marines.

Gray told Myatt that spec ops were “after our platforms,” the amphibious ships that enabled Marines to do Marine things with the Navy.

To beat back that subterfuge, Gray was leading the creation of an organic “hostage rescue capability” in the MEU.

And this went beyond ships.

“Furthermore, (Gray) said that the Marine Corps could not afford to be in a situation where, for example, if hostages were taken at Camp Lejeune and held in the Base CG’s headquarters building, we would have to depend on JSOC to deploy to Camp Lejeune while the Marines sat idly by, watching the ‘terrorist throw hostages out the windows,’” Myatt wrote.

Gray listed all kinds of missions he wanted the Marines capable of doing over-the-horizon nighttime amphibious raids, both surface an heliborne; noncombatant evacuation, security ops, extended range raids, mobile training teams to work with foreign military forces, initial terminal guidance to bring in heliborne forces to a site at night, deception operations, electronic warfare and disaster relief, to name a few.

Sound familiar?

It’s basically a review of what Marines on MEUs, in reconnaissance and even line infantry units are doing pretty much daily in 2021. That was not standard in the mid-1980s.

The future commandant was realistic in his aim, though.

“Not every Marine can be trained for Force Recon, he said; but, all Marines can be trained to have the necessary mindset!’” Myatt wrote.

And then Gray set a high standard.

“He said that a well-trained, forward deployed, special operations cable (MEU) should be able to commence operations on a mission within 6 hours after receiving the mission,’” Myatt wrote.

The old days of taking 30 days to plan a raid, as it said in FMFM 8-1 “Amphibious Raids” were gone.

One year later, Gray was a three-star and heading II Marine Expeditionary Force. Myatt had new orders in hand.

He arrived to learn that the 24th MAU, then off the coast of Lebanon, had been ordered to offload helicopters and Marines from their ships to “make room for JSOC” so that special operators would have space to run hostage rescue missions.

“General Gray’s prediction had come true,” Myatt wrote.

Training commenced, with a vengeance.

In 1985, then-Col. Myatt would command the 26th Marine Amphibious Unit, a precursor to the MEU, and the first Marine unit to achieve the SOC designation.

But where would they train? The only sizable facilities were on Army installations.

Gray had a plan.

Inside those same archive papers, another Marine officer, Col. Mike Williams, wrote about one late afternoon in the winter of 1986 while on duty at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

A young lance corporal from admin came knocking on his office door.

“Sir, there is an old guy out in the hallway who has a Marine Corps utility uniform on, no rank insignia, and he looks like he hasn’t shaved in three days. He says he knows you and needs to talk ASAP,” the lance corporal said.

“I scratched my head trying to think of who the hell this could be and then it came to me — only one Marine has the rep and balls to show up anywhere that way — Col. Patty Collins,” Williams wrote.

Collins rumbled into Williams’ office with a stack of paper and a map of Camp Lejeune.

“Papa Bear (Gray) has sent me down here to talk to you about making a compound for a new initiative of his (MEU(SOC)) — and he wants here at Camp Lejeune in an isolated area away from main side so special people can do special things without being jerked around by weenies. Can you help me?” Collins asked.

There was an old World War II compound hidden back in the Lejeune woods that had been used to house German POWs during the war. It was about to be demolished to save on maintenance costs.

“I threw Patty into my truck and we raced down to see what was now only half of the original compound,” Williams wrote. “With pencil and paper and using his reconnaissance skills for drawing sketches of key terrain and built-up areas, Patty quickly had a diagram and a plan for the new home of the new MAU(SOC).”

Williams had his own takeaway on Gray’s influence.

“He anticipated the ascension of asymmetric warfare before the rest of us ever heard of it much less could spell the term,” Williams wrote.

Adding to the laundry list of taskers, the MAUs-turned-MEUs added tactical recovery of aircraft and personnel, or TRAP, missions and gas oil platform takedowns to their portfolio.

Both of those skill sets came in quite handy a few years later, making international headlines.

In 1987, a Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force commanded by Col. Bill Rakow in the Persian Gulf was asked to take down an oil well platform that Iranians were using for weapon emplacement to disrupt oil tanker traffic.

“From the time Col. Rakow got the order, he was given a ‘go-time’ of six hours, and he made it on a very successful operation,” Myatt wrote.

The six-hour rule would surface once again in our final historical example.

Myatt called the success of that response time a “hugely significant factor” when the 24th MEU(SOC), note the “SOC” part, got a call in June 1995.

That was when 51 Marines with 3rd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment boarded two CH-53 Sea Stallions to rescue downed Air Force fighter pilot Capt. Scott O’Grady, who’d been evading capture for seven days in Bosnia while conducting air operations.

“They were assigned the mission because they honestly said they could do it within the allotted time, where the SOF forces wanted three days to plan that mission,” Myatt wrote.

Six hours indeed.

*Correction: This article has been corrected to reflect the rank of Air Force Capt. Scott O’Grady.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.